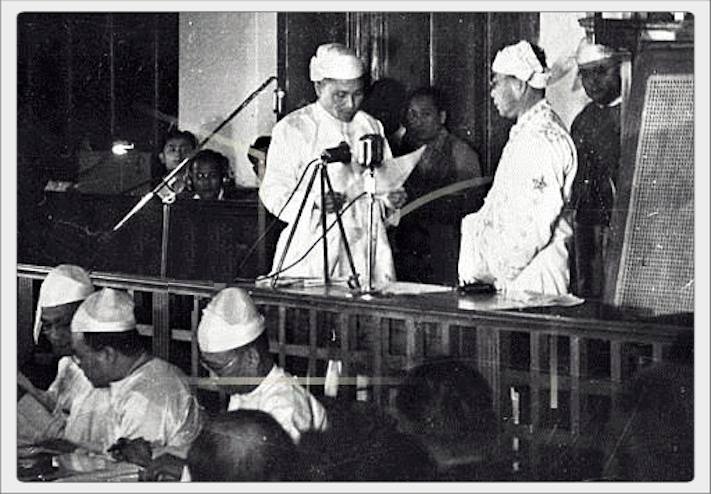

President Sao Shwe Thaik and Sir Hubert Rance at the first Independence Day ceremony

Thakin Nu sworn in as the first Prime Minister by the first President Sao Shwe Thaik of Yawnghwe

4 January 1948

Myth of Burma Independence

people U Nu Sao Shwe Thaik Sir Hubert Rance

On 4 January 1948, at 4:20 am, Burma became an independent republic outside the British Commonwealth. The Union Jack was lowered for the final time at Government House in Rangoon and the last Governor Sir Hubert Rance formally handed over power to the Union of Burma's first president the Saopha of Yawnghwe, Sao Shwe Thaik.

There is a myth that Burma at independence had all the attributes of a country fated for prosperity. But the country in January 1948 was actually in ruins after five years of war between the Allies and the Empire of Japan. Every port, airport, oil refinery, railway line, station, bridge, and factory had been destroyed or severely damaged. Entire towns including Mandalay had been razed to the ground. A generation of children had missed years of school, seeing only war all around them, and hundreds of thousands of IDPs were camped in makeshift homes. The countryside was awash in weapons and within just a few short months, would become a patchwork of insurgencies and militia. The Mujahideen soon took control of northern Arakan (Rakhine State) and a communist uprising swept through urban centres throughout Burma. Within a year, fighting between the Burma Army and the Karen National Union would reach Insein on the outskirts of Rangoon.

The government at the time was young (average cabinet member in his 30s), well-meaning, and energetic, but lacking in any administrative experience. There were several distinguished civil servants, barristers, judges, scholars, and soldiers, but far too few for a country of Burma's size and population. The British had expected to stay another 5-10 years and so had not really prepared a proper transition.

To better understand Burma's transition to independence (and soon after, civil war), it's important to remember what else was happening in the world.

In early 1948, nearly the entire world was in ferment. The Cold War was in full swing, with preparations underway for a new North Atlantic Alliance against the Soviet east. The Soviets were blockading Berlin, bringing the new Cold War to near boiling point and the United States would soon approve its "Marshall Plan" to rebuild a war-destroyed Europe. The United Nation's Palestine Mandate was just about to end, leading to the birth of Israel in May 1948 and, almost immediately afterwards, the first Arab-Israeli War. Meanwhile, Korea was about to be divided between North and South, and the communist revolt against the new Federation of Malaysia was soon to erupt, leading to the "Malayan Emergency" and 12 years of guerrilla war with the British. The First Indochina War was in full swing, with the French fighting the Viet Minh, and Dutch forces were in the middle of a four-year battle against the new Indonesian republic.

Most importantly for Burma, British India had just been partitioned into the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan. Partition led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people and the first India-Pakistan War over Kashmir. Burma no longer bordered any British possession. At the same time, China's civil war was in its closing chapter and, by late 1949, the communists would seize Peking and declare a new People's Republic. The remnants of the defeated Chinese nationalists would cross into the Shan states, igniting a new round of violent conflict. For years, American "Cold Warriors" supported the Chinese nationalists, whose aim was to attack communist Yunnan from Burma. The uplands of Burma have not known real peace since.

British Prime Minister Clement Attlee's reformist Labour government succeeded Winston Churchill's conservatives in 1945, promising change in the UK and deciding quickly on decolonization in Asia. By 1946, Burma's usefulness to the UK was over; it was no longer a strategic eastern buffer for British India, and it was clear that its ruined economy would take years, if not decades (and lots of money) to recover. Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong were key to future profits for UK companies, not Burma. By early 1947, the UK government was looking for a way out of Burma. The Burmese independence movement helped determine the shape and exact timing of independence but there was little doubt the British would leave sooner rather than later. On 4 January 1948, the British quit Burma for good. For the Burmese, it would be a brave leap into the unknown, at a time of global turmoil.

Overcoming this myth of a lost golden age and appreciating Myanmar's ever-changing international context is important in facing more clearly the scale of the challenges ahead. The images are of President Sao Shwe Thaik and Sir Hubert Rance at the first Independence Day ceremony; Thakin Nu sworn in as the first Prime Minister by the first President Sao Shwe Thaik of Yawnghwe; and Map of the British Commonwealth in 1948.